My shopping cart

Your cart is currently empty.

Continue ShoppingWith Rover Day II coming this Saturday the 22nd, we thought it would be appropriate to share the following story by Ben Fogle of The Telegraph about how this iconic truck came to be. Hope to see you at our Hunt Valley location this weekend.

Reporter and Author of a Land Rover book: Ben Fogle

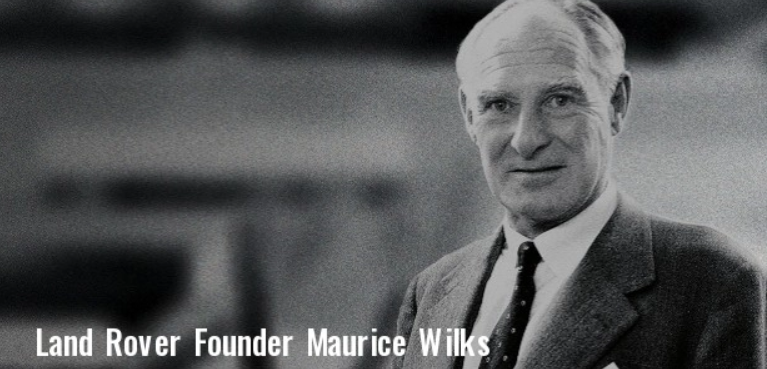

In the overgrown graveyard of St Mary’s Church at Llanfair-yn-y-Cwmwd, on the Isle of Anglesey, North Wales, is the weathered gravestone of Maurice Wilks, on which the inscription reads: “A much loved, gentle, modest man whose sudden death robbed the Rover company of a chairman and Britain of the brilliant pioneer who was responsible for the world’s first gas turbine-driven car.”

Like the man himself, the inscription is modest, for it fails to mention the invention for which he is best known, the Land Rover.

Wilks died in 1963, aged just 59. In his all-too-short life he also helped to develop Frank Whittle’s original jet engine, but he will forever be remembered for creating the motor car that took the world by storm. Nobody back in the Forties, Fifties and Sixties could have predicted how the utilitarian 4x4 would one day become the car of the stars.

When Wilks died, even his family underestimated the importance of the Land Rover. They thought he’d be best remembered for his contribution to Rover’s ill-fated gas turbine car, which is why that got mentioned on his gravestone and the Land Rover didn’t.

Wilks, engineering director at the Rover car company, owned a rugged 250-acre coastal estate at Newborough, on Anglesey, which was made more accessible thanks to his own ex-US Army Jeep. Whenever he was able to escape the hustle and bustle of Rover’s factory for the wilderness of Anglesey, the man and his machine were seldom parted.

One day, his brother Spencer, Rover’s managing director, asked him what he would do when the battered warhorse eventually wore out. “Buy another one, I suppose. There isn’t anything else,” was his fateful reply.

Legend has it that the Wilks brothers were relaxing on the beach at the time – at Red Wharf Bay in Anglesey, to be precise – and Maurice began drawing a picture of his ideal 4x4 in the sand. Unsurprisingly, it looked very much like his Jeep. It wasn’t long before the rough sketch became reality, though, for the brothers reckoned there was a niche for a civilian version of the Jeep, and they decided to build it at Solihull.

Again, circumstances played their part. With steel strictly rationed, Rover decided to create the new vehicle’s bodywork from Birmabright aluminium alloy panels. The steel box-section chassis was born of necessity, with strips of steel cast-offs hand‑welded together to create a ladder frame. As well as being cheaper to install than heavy pressed or expensive sheet steel, it also achieved the level of toughness appropriate for an off‑road utility vehicle.

Astonishingly, the same basic ladder-frame chassis was used throughout the production of the Series Land Rovers, as well as the Defenders, until the manufacture of the last cars in January 2016.

The ladder-frame chassis was also the backbone of the first and second-generation Range Rovers (1970-2002), Discovery 1 and 2 (1989-2003) and the various military and other special models produced at Solihull.

The new 4x4 planned by the Wilks brothers also had great export potential. In 1947, British children still toiled in classrooms in which maps of the world showed more than half of the land mass coloured pink, denoting countries that were either British colonies or former colonies (by then part of the British Commonwealth).

The sun had not yet set on the British Empire and there were plenty of colonial outposts in the developing world where Rover’s projected all-terrain vehicle would prove an invaluable mode of transport. So although the first Land Rover was designed with the British farmer in mind, its versatility meant it would be a brilliant workhorse anywhere on the planet where the going was likely to get tough.

And it still is. For example, in the remote Cameron Highlands of Malaysia, extremely battered Land Rover Series Is are even today the main mode of transport in the tea plantations, including some very early 80in models, which would be worth a fortune as “barn finds” in the UK.

The introduction of the Land Rover marked a fresh start at the company’s new Solihull premises, and the enthusiasm of the management for the vehicle was such that it even axed its plans for its projected M1 “mini” car, which had reached prototype stage by 1946, in favour of the newcomer.

The first Land Rover prototype was built in the summer of 1947, using many parts (including the chassis) from a Willys Jeep, while the engine was an underpowered 1,389cc unit from a Rover saloon. The car differed from the Jeep in that it had a more cramped driving position, because Rover wanted to provide the largest possible payload area in the back and so moved the driver’s seat forwards three inches to achieve it.

Comfort was rudimentary: just a plain cushion in the middle of the metal seat box, which also covered the fuel tank. With exports in mind, it had a tractor-like, centrally mounted steering wheel to save building separate left- and right-hand-drive models. Thus it became known as the Centre-Steer.

Today, the Centre-Steer prototype is the holy grail to many Land Rover enthusiasts. That’s because apparently no trace of it exists, although some very respected Land Rover experts are convinced it does. In fact, some believe several Centre-Steers are secreted away somewhere.

Rover’s engineers quickly realised that the Centre-Steer wasn’t a viable proposition and opted instead for the conventional wisdom of separate right- and left-hand-drive vehicles. Although the development engineers borrowed some ideas from the Jeep – notably the 80in wheelbase – the parts for the new vehicle were all designed and built by Rover. Work continued through 1947 and in February 1948 they began to build the first pilot prototypes.

It had been decided that the new vehicle – by now christened the Land-Rover (note the hyphen, which wasn’t lost until a decade later) – would be launched at the Geneva motor show in early March, but it soon became clear that the prototypes wouldn’t be completed in time, so it was decided that it would be revealed at the Amsterdam motor show instead.

Thus it was, in the Dutch capital, on April 30 1948, that the Land Rover legend was born when two prototypes – left- and right-hand-drive variants – went on display. One was a standard model, the other equipped with PTO (power take-off)-driven welding equipment, to demonstrate the versatility of the strange-looking little vehicle.

The initial 80in wheelbase Land Rovers that were sold to the general public remained very agricultural in every respect. Heaters were non-existent, as were passenger seats, door tops and roofs, but that hardly mattered because cabs and hard tops were yet to be introduced and Solihull’s new arrival was intended to be very much open plan, with the driver exposed to the elements.

Nothing unusual there; contemporary tractors, combine harvesters and other farm machinery of that era didn’t have comfortable cabs either.

Nobody minded the Spartan comforts, once they encountered the new vehicle’s capabilities. They didn’t even bat an eyelid when the original purchase price of £450 was jacked up to £540 in October 1948.

The first year’s production was 3,048, but this more than doubled to 8,000 the following year, doubling again to 16,000 in 1950.

What had been seen as a stopgap exercise, cobbled together from Rover car components and other bits copied from the original Jeep, was now an important vehicle in its own right, and one that would eventually outsell – and indeed outlive – Rover cars.

Thanks to Maurice Wilks, the company clearly had a success story on its hands.